Source: Music of the Avant-garde, 1966-1973

Edited by Larry Austin and Douglas Kahn

University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, 2011

Directed by Larry Austin and Douglas Kahn, both former teachers at UC-Davis, this long-awaited anthology published by U. of Cal. Press, gathers a generous selection from the 11 issues of Source, but is not a complete reprint, as original color pages, photo essays and material printed on transparencies or fur had to be set aside for practical reasons. Printed in black and white, in a format reduced by 1/3rd compared to the original magazine, the book is still a wonderful complement to the Pogus 3xCD set issued by Al Margolis and restoring the six accompanying 10-inch LPs, including such classics as Robert Ashley’s The Wolfman, Alvin Lucier’s I Am Sitting In A Room or Annea Lockwood’s Tiger Balm. See the revamped Wikipedia article for an introduction to Source.

Above: NY Corres-Sponge Dance School of Vancouver, Source logo, Ken Friedman

Source Magazine emerged in 1967 after an incredibly creative decade in the Bay Area and a series of buoyant, multifarious initiatives in the fields of improvised music (Lukas Foss’ Improvisation Chamber Ensemble, the Pauline Oliveros/Terry Riley/Loren Rush 1958 improvisations for a Claire Falkenstein film); electronic music by Morton Subotnik and the San Francisco Tape Music Center; intermedia art (Herbert Blau’s Actor’s Workshop, the San Francisco Mime Troupe and choreographer Ann Halprin all collaborated with experimental music composers); performances and Fluxus events by Allan Kaprow or La Monte Young; etc. Various institutions helped disseminate and stage these groundbreaking sound experiments: Mills College where Subotnik was a teacher and Steve Reich a student in 1961 ; UC Berkeley’s Department of Music, home of the Noon Concerts series ; the San Francisco Conservatory organized its Sonics series in 1961-62 ; Charles Amirkhanian’s influential avantgarde music broadcasts on KPFA radio ; the Morrison Planetarium’s Vortex, etc.

FROM POLITICAL TRACT TO GRAPHIC SCORE

This was also a time of high political activism, none more visible than UC Berkeley’s anti-Vietnam war protests. Similarly, protestation and vindication prompted Larry Austin and Source’s editorial team to promote the most radical forms of music and indeed, says Austin, ‘rejection and dissent pervade these works’ (preface to issue #1, p12 – all page numbers from the book under review). An experimental music magazine created as a protestation against conformism and institutions, Source challenged formal concert performances and traditional music scores in every possible way. ‘The score no longer serves as a roadmap’, writes Will Johnson in issue #3 (p123), and ‘composers reject the notion of traditional score’.

But rejection would be nothing if it were not to support a new paradigm and this is why Source editors believed in the power of graphic scores to champion their conception of new music and their faith in music’s freedom. The magazine soon became an extraordinary kaleidoscope of drawings, artworks and photos, whose design alone, arguably, prompted many subscriptions. With good reasons, Austin is proud of the graphic work: ‘We wanted to make Source an artwork and I think we succeeded in that regard’ (p8). Not only was the score considered a document or report of possible musics, it also signaled ‘the transition between literary music and performed music […] and machine-generated music’ (Austin, issue #5, p202), which was the reason Source focused so much on graphic scores, as it enabled the notation of improvised, performance and electronic musics, new genres traditional notation couldn’t properly document.

THE COMPOSER AS TECHNICIAN

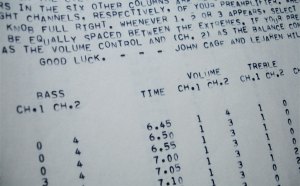

Above: Alvin Lucier, Lowell Cross, John Cage/Lejaren Hiller

More than any other music magazine, Source heralded the new role of the composer in the electronic age. Reporting on a performance of Alvin Lucier’s Music For A Solo Performer in issue #2 (p79), Gordon Mumma details the various actions of the ‘technical assistant’ ensuring ‘musical continuity’ between the performer’s brain Alpha-waves and the Cybersonics amplifier, and the complex ‘system-concept thinking’ underlying Music For A Solo Performer. For Will Johnson, writing about the same sound work, the composer is now a technician and an explorer (p117); for Larry Austin, a practitioner or a synthesist (p202). Though it seems natural for artists to explore the technological possibilities of the era, why would they refuse being considered as composers? Perhaps because, in the 1960s, the US universities and music conservatories were already shock full of composers of all kinds and such enviable positions were not available to newcomers. They had to create a niche for themselves in the music world, as suggests Ben Johnston in his article on the state of institutional music in issue #7 (p250), one of the best essays in Source, along Dick Higgins’ Boredom and Danger in issue #5 (p178).

While electronic music was all the rage in the Bay Area since the late 1950s, Source magazine helped demonstrate its validity as a genre, a repertoire and a respectable art movement. In addition to pure electronic music, Source also championed hybridized forms of art involving two or more disciplines, as well as intermedia arts, a term coined by Dick Higgins to describe the fusion of different techniques to create a new art form (p239). Coincidentally, Source is the exact contemporary of the legendary Art & Technology group exhibition curated by Maurice Tuchman and Jane Livingston at Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1971, which brought together international contemporary artists and Californian corporations.

MEANWHILE, OFF SOURCE

It’s easy to feel dizzy contemplating the long list of artists included in Source along the years, yet the number of set aside, like-minded artists is also significant. As Larry Austin remarks, some artists could not be included for legal reasons – with publishers, say – but the ‘not-included’ artists form a group that can help define the actual scope (and limitations) of Source. For instance, Takehisa Kosugi’s Fluxus performances, Henry Brant’s spatialization concept of the 1950s, George Crumb’s graphic scores, Tod Dockstader’s electronic music, Alison Knowles’ computer poems and sound installations, Harry Bertoia’s sound sculptures, or Jean Tinguely’s 1960 Homage to New York, all seem to fit in the magazine’s canon.

The graphic score proved an adequate medium for 10 or 20 years, but was eventually superseded by sound installation, sound art and abstract electronic music where a score is less relevant. Since then, it has been steadily losing momentum as an inflammatory and subversive medium, to the point of becoming a mere decorative by-product of music composition. In a final analysis, the graphic score belongs to a time when music composers wanted to enter the art gallery, for want of a better place to perform their art. Part of Source‘s remarkable accomplishment lies in documenting and contributing to this highly creative, if short-lived, period.

* *

*